GIVE THIS RAMADAN

This opinion piece by Onome Ako, Action Against Hunger Canada’s CEO, was originally published by the Hill Times.

In humanitarian aid, the world is now doing what emergency doctors do when

overwhelmed: choosing who to save and who to leave behind.

This logic of triage, once limited to disaster zones and field hospitals, has become the organizing principle of global foreign aid. Faced with shrinking resources and waning political will, international donors are increasingly focusing only on the most catastrophic crises—those where lives are at risk. Everything else, from food security to education to economic development, is being sidelined.

Sweeping aid cuts made under the Trump administration are driving this shift, with cuts to foreign aid totalling $49.1-billion, including $4.7-billion in non-food humanitarian aid, $6-billion from global health programs, and $8.4-billion from economic development. The United States once accounted for 42 per cent of international aid. Its retreat has undermined every aspect of delivery, including logistics and infrastructure.

Several European countries have followed suit, and Canada announced plans to cut aid spending in its November 2025 budget. According to Oxfam, the most recent G7 aid reductions are the steepest since records began in 1960.

The results of these fundamental shifts have forced the United Nations to make its deepest-ever cuts to humanitarian assistance, nearly one-third of its entire aid spending.

As the UN’s top humanitarian official Tom Fletcher put it: “We have been forced into a triage of human survival.”

Fletcher called the math “cruel, and the consequences are heartbreaking. Too many people will not get the support they need, but we will save as many lives as we can with the resources we are given.”

Much like emergency triage, priority will go to regions facing extreme or catastrophic conditions. With limited resources, areas deemed less urgent but which still have

extremely high needs may receive no support at all. Countries such as Cameroon, Colombia, Eritrea, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, and Zimbabwe have already started to be cut off from support, which will result in millions of unnecessary deaths.

The implications are grim. This shift means that global aid will focus almost entirely on emergency response, with limited capacity to prevent or mitigate the underlying drivers of the crisis.

To put it in Canadian terms, it’s like boosting food bank funding while abandoning job creation, or fighting wildfires without investing in fire prevention.

The irony is that the most effective and cost-efficient aid is preventative. The goal of development spending has always been to help countries reach a point where they no longer require aid, becoming self-sufficient and economically productive. That’s why countries like Canada have long invested in healthcare, agriculture, and education across the global South.

Moving to a crisis-only model risks locking low- and middle-income countries into permanent instability. It doesn’t reduce long-term costs. It guarantees them.

To those who cry “waste” every time aid is mentioned, ask this: What’s more wasteful: sending emergency rations to a country in constant famine, or helping it build food systems that prevent hunger in the first place?

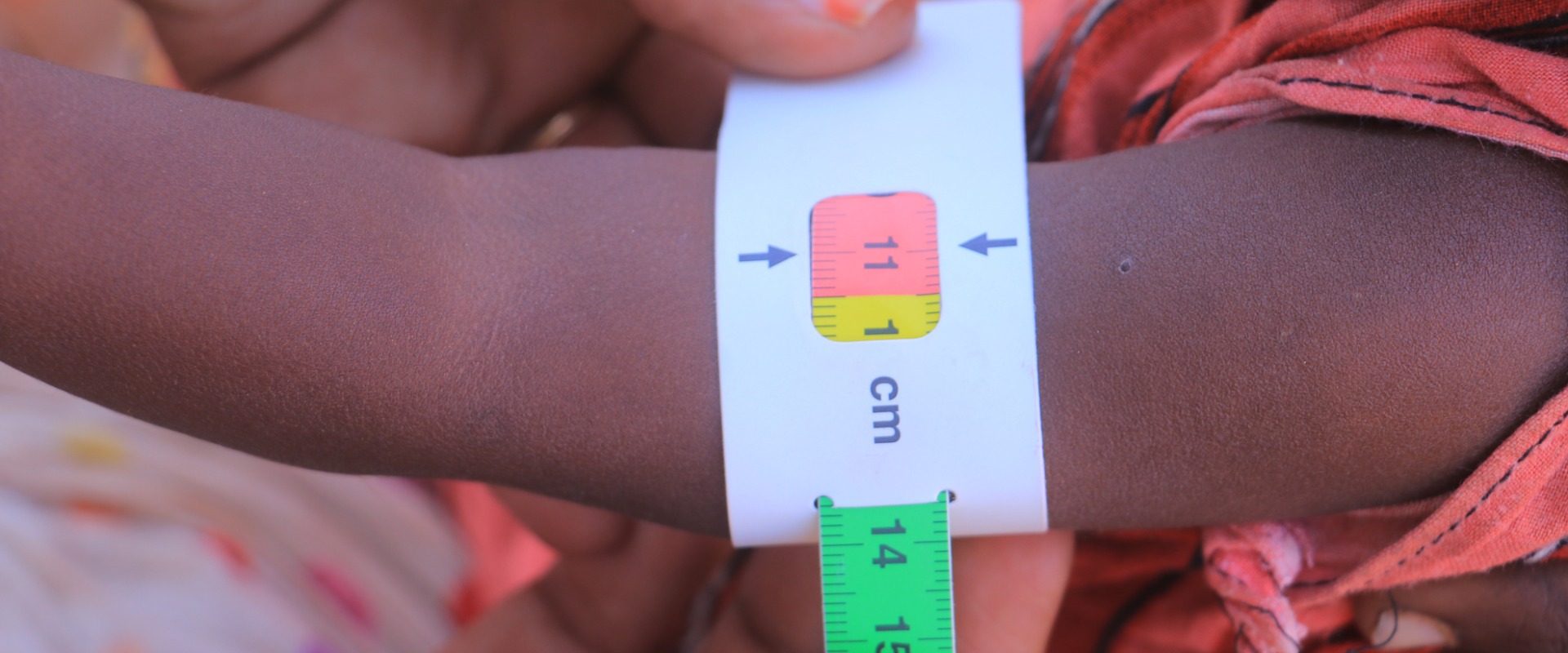

The need is real. According to the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2025 report, 673 million people are hungry, and more than 2.3 billion people are experiencing moderate or severe food insecurity. One in five people in Africa is undernourished. An estimated 150 million children under the age of five are affected by stunting, and millions more suffer from wasting, the deadliest form of malnutrition.

This is a pivotal moment for Canada, which has rightly resisted deep cuts to development spending so far. But how we deliver aid may need a fundamental rethink.

Action Against Hunger Canada, alongside Canadian Partnership for Women and Children’s Health recently brought together leading global nutrition experts for a two-day retreat to consider a path forward within this radically changed environment.

Participants recommended four interconnected priorities for Canadian aid: deliver life-saving nutrition services and protect the critical infrastructures and systems needed to provide them; bridge the divide between humanitarian response and long-term development; build predictable and diversified financing models; and advance locally led actions to ensure sustainability.

This is the roadmap to moving beyond a triage approach to aid, and Canada has the nutrition expertise to lead this effort.

Where Canada once followed, we now have to lead. As Prime Minister Mark Carney stated in his speech to the World Economic Forum back in January, intermediate powers like Canada have the capacity to build a new world order that encompasses our values.

This work must start now when it comes to foreign aid. Triage is a tool of last resort. It should never be the foundation of foreign aid policy.

By Onome Ako, CEO of Action Against Hunger Canada (originally published by the Hill Times)

Join our community of supporters passionate about ending world hunger.